Wealth Taxes III: Problems

The fourth and fifth briefs will deal with international experience, the sixth with a land tax, and the seventh with lessons for South Africa.

Introduction

This brief deals with the problems with wealth taxes and is broken into five sections: (1) Ways in which wealth taxes may be inequitable, (2) A heavy burden on the middle class, light on the rich, (3) The complexities of administration and high cost of collection, (4) Low revenue, and (5) Unintended consequences.

Ways in which wealth taxes may be inequitable

Wealth taxes are to some an intrusion on private property when compared to income taxes. With wealth taxes, the government has a claim against a taxpayer’s net assets, no matter whether the assets have generated an income or not. [1]

Narrowly defined wealth tax bases require higher tax rates to generate substantial revenue, reinforcing discrimination between asset types. [2] On the other hand, wider tax bases make it more difficult to prevent evasion, which in turn increases inequalities between taxpayers with different degrees of honesty. [3]

Consider two people with equal life spans, levels of starting wealth and continuing income, but different savings and asset disposal/transfer rates going forward. The person who saves more and disposes/transfers his/her assets more slowly will pay more wealth tax. [4] The person who does the opposite will be paying more VAT and other wealth-type taxes as discussed in the first brief. Thus an in depth cost benefit analysis will be required to try mitigate any inequities.

Some argue that the main benefit of holding wealth is insurance against shocks to human capital. If so, a wealth tax rate that doesn’t decrease with age discriminates against retired and older people who have much less human capital. [5]

Furthermore, the acquisition of wealth is a function of the 'life cycle,' i.e. the usual point of maximum net wealth is just as we retire: mortgages are paid off and pension savings is at its greatest. Thus net wealth taxes will have a disproportionate effect on senior citizens on the verge of retiring. [6]

Human capital is nearly impossible to tax, but excluding human capital from wealth taxes can be inequitable as the following scenario shows:

Consider two individuals Peter and Kate. Peter inherited his wealth in the form of bonds, consumes the interest payments and has no other income. Kate has no savings but has an excellent qualification and a job with a long term contract. Assuming the present value of Kate’s future pay equals the value of bonds held by Peter, a wealth tax on financial assets and not human capital discriminates against Peter who will not be able sustain the same level of consumption as Kate. [7]

Wealth taxes are double taxation when wealth consists of saved incomes that were previously subjected to income tax. Double taxation however is not unique to wealth tax as VAT is paid on goods and services out of taxed income.

A simple flat-rate wealth tax structure, i.e. non-progressive, discriminates against taxpayers at the lower end of the wealth scale who still need to build up wealth for savings and retirement. This feeds well into the next section. [8]

Heavy burden on the middle class, light on the rich

Surveys in the UK show that the middle class are most resistant to a wealth tax, because as one might expect, they have the strongest desire to leave as much of their limited wealth as possible to the next generation. [9]

The middle class tend to have most of their wealth tied up in an immobile and tangible asset, their home. The rich however have their home and other far more liquid and intangible assets. These additional assets owned by the rich are significantly more difficult for the authorities to tax, for reasons discussed later this brief, which has resulted in chronic tax avoidance by the rich globally.

Fast rising house prices can bring more middle class into the wealth tax net. A more middle class friendly wealth tax system would therefore require an exemption threshold that adjusts along with house prices.

House price revaluation is costly and will be borne more heavily by middle class taxpayers, especially those living in an area with few housing market transactions. [10]

What if lived in family homes were exempt from the wealth tax? This unfortunately would provide a strong incentive to borrow against other chargeable assets to invest in the home. It may also lead to older taxpayers who should be in sheltered accommodation choosing to stay home because of the tax break. [11]

As mentioned above, the rich are better equipped to take advantage of tax avoidance and even evasion opportunities that occur mostly though cross border transactions. For this to be reduced an international consensus on a wealth tax regime would need to be reached. Currently there is no agreement amongst the revenue authorities about the taxation of wealthy individuals. [12]

The lack of cooperation among countries in setting tax policies is fully intended and known as mercantilism: governmental regulation that promotes a nation's economy for the purpose of augmenting state power at the expense of rival national powers.

One careful estimate is that there is about US$4.5 trillion in unrecorded household assets located in tax havens. [13]

The effectiveness of a wealth tax thus rests largely upon effective limitations to tax shelters available to the rich, possible only if there was unfettered cooperation and information exchange between governments worldwide.

Lastly, due to the challenges and inefficiencies in taxing difficult to value or locate assets held by the rich, it has been suggested that some of these assets should be excluded from the wealth tax base. Such a partial approach however is plainly inequitable and might worsen wealth inequality instead of reducing it. [14]

The complexities of administration and high cost of collection

Wealth taxation requires regular asset valuations that impose additional costs on taxpayers and increases admin costs for the receiver of revenue.

Taxpayers will incur the costs of valuing his/her assets just to ascertain whether or not he/she is liable for wealth taxes. [15]

For any receiver of revenue, valuing assets within a taxpayer’s wealth portfolio is an expensive and difficult task. Furthermore, valuations are often speculative and easily manipulated, resulting in disagreements between the taxpayer and the receiver. This creates difficulties for both parties in planning ahead. To try and mitigate this, annual taxes could for example be charged on valuations done every five years.

Fortunately the cost of processing asset valuation information has been rapidly declining thanks to advances in information technology. [16]

Wealth taxes raise potential liquidity issues for taxpayers. The assets being taxed might not produce the income necessary to pay the tax and the owner will need to find funds elsewhere. If they cannot, he/she will have to sell part of or the entire asset, ultimately resulting in an erosion of equity.

Those arguing against the liquidity issue assume that a progressive wealth tax will sufficiently mitigate the problem because wealthier individuals are more likely to receive higher liquid incomes. It may be further mitigated, they say, by a deferral of the tax liability (to the moment of liquidation for example). [17]

If works of art have to be sold because of liquidity issues it could lead to a dispersal of national heritage. In France therefore works of art are exempt from wealth taxes. [18]

A 2015 study by the European Commission on Wealth Distribution and Taxation in EU member states found that wealth tax policy approaches tended to be piecemeal or incomplete. This, the study stated, obscured the wealth tax policy debate and challenged the introduction of wealth taxes. [19]

In order for the taxation of wealth to gain political support, the public will need to perceive the benefits of publicly provided goods financed by wealth taxes in mitigating socio-economic inequality. Public administration and tax-benefit systems that deliver both on efficiency and fairness are cornerstones of wealth taxation. Special fiscal mechanisms, such as earmarking wealth tax receipts to fund specific projects instead of plain redistributive spending, might also enhance the acceptance of wealth taxes. [20] Furthermore, because a system of taxing wealth has to operate over a person’s lifetime and is vulnerable to changes in government, to be effective there must be political consensus on how wealth is taxed. [21] It thus follows that if there is no political consensus, a tax payer who believes that wealth taxes will change with a change in government will try and delay declaring his/her wealth. [22] Finally, the tracking of ownership of mobile assets might be seen by some with suspicion for fears of coercive wealth levies. [23]

Globally, there is a lack of reliable household wealth distribution data as well as great difficulties in predicting behavioral responses to wealth taxes. These two factors mean that any analysis of the effects of changes in the taxation of wealth will be speculative and potentially dangerous if acted upon. [24]

Low revenue

Historically, revenue from net wealth taxes has been low in countries applying them, ranging from 0.07% to 5% of total national revenue [25]. In the South African context, Judge Dennis Davis of the Davis Tax Commission is quoted as saying “I would be very surprised if a wealth tax brought in more than R5 billion a year.” [26] This would come to 0.44% of the R1.144 trillion total revenue for the 2016/17 tax year.

Evasion and difficulties of asset valuation have been considered key in reducing the revenue generating capacity of wealth taxes. [27] Thus zero-tax allowance thresholds have been suggested to lighten administration. However, if these thresholds are too high it will jeopardize the production of revenue. [28]

Due to the moderate revenue it generates, wealth taxes can contribute only minimally to reducing inequality. The Swedish government, which abolished wealth taxes in 2007, said they found their performance disappointing in terms of both revenue and perceived impact on inequality. [29]

In 2010 the Institute of Fiscal Studies in the UK released a report on the then current system of taxing wealth in the UK and the potential for the introducing a net wealth tax. The following is an extract from the study:

Such a major change in the tax system needs to be justified by a sufficient margin to outweigh the costs of change, and it is far from clear that the advantages of a wealth tax are sufficiently great to justify the risk of such a change. For example, the yield of wealth taxes in countries such as France has not been significant. [30]

Unintended consequences

A 2008 study titled The Economic Consequences of the French Wealth Tax, by Professor Eric Pichet of Kedge Business School, found that France loses around 5 billion Euros in tax revenue a year because of people leaving to avoid the wealth tax. Pichet goes further to say this capital flight could cost at least 0.2% of annual GDP due to a decrease in investments.

Since 2000, France has experienced a net outflow of around 60 000 millionaires. Vincent Lazimi, a partner at law firm Vaslin Associés, says “There has been an acceleration of departures from France due to the unstable nature of the policy (wealth tax).” [31]

This all leads well into the following paragraphs on wealth taxation’s effect on tax evasion, savings, investment, entrepreneurship and ultimately growth.

Only net wealth is taxed, and because of this taxpayers will be incentivized to avoid the tax by borrowing against his/her assets and investing the funds in a jurisdiction or asset that is exempt from wealth tax. [32]

In Switzerland where wealth taxes still exist, a group of economists recently found that wealth taxes there substantially reduced reported wealth holdings as taxpayers aimed to get their wealth to just below threshold levels at which they will not be liable for wealth taxes. [33]

To limit evasion and avoidance, an international consensus on wealth taxation would need to be reached, an extremely difficult task. Technology too has made it easier for funds to be shifted at low cost around the globe, and while this has contributed to tax evasion, the World Economic Forum argues that it may also help fight it if authorities have access to the right data, technology and laws are adapted to the new realities. The recent OECD and G20 initiative on base erosion and profit sharing, the WEF says, is a welcome first step. [34]

The 2015 European Commission report on Wealth Distribution and Taxation in EU Members as well as the 2016 German Institute for Economic Research report on Inheritance Tax and Wealth Tax in Germany both conceded that the introduction of a wealth tax could result in capital flight. In fact, when net wealth taxation was abolished in Ireland and Holland, the most important reason given by those governments was capital flight. [35]

Savings and investment decisions may become distorted as a result of wealth tax.

Savings could decrease as taxpayers are incentivized to substitute future consumption with present consumption, causing efficiency to suffer. Also, the allocation of savings between different investments may be distorted if they are subject to different taxes. [36]

It may not be obvious at first, but if a tax payer’s net assets earn a return of 3%, a 1% wealth tax is a 33% tax on that return. [37]

Wealth tax also increase the required rate of return on investments. Consider a potential investment with a required return of 5% and wealth tax at 1%. To make the investment viable, the equilibrium required return then becomes 6.05%. This is a 21% increase in the required return due to the wealth tax. [38]

Individuals might become more discouraged than before from making risky investments because wealth taxes automatically increases investment risk. Under income tax, a taxpayer can write off investment losses against gains when calculating taxes owed. Thus government indirectly shares in the investment risk. This however doesn’t happen under wealth taxes. When an investment in a wealth tax system experiences a loss, government is unaffected because the taxpayer is still required to pay the full amount, thereby exacerbating the loss. [39]

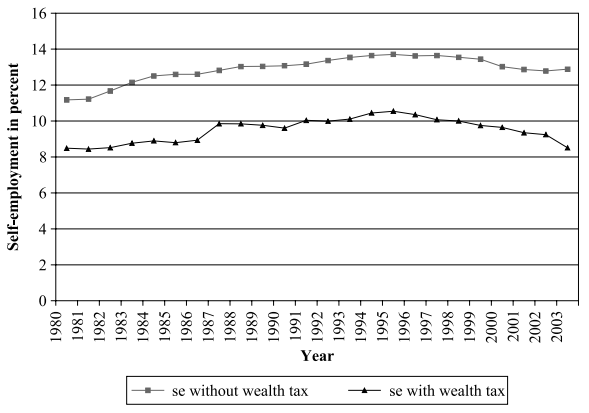

Finally and empirically, wealth taxes have a negative impact on entrepreneurship. The following is taken from a 2008 study, The Wealth Tax and Entrepreneurial Activity by Lund University’s Asa Hansson:

Data from twenty-two OECD countries indicates that countries that do not tax wealth have systematically higher self-employment than countries that do tax individual wealth. Average self-employment, indeed, was 24 per cent higher in countries without a wealth tax than in countries that taxed wealth over the time period 1980 to 2003.

Average Self-employment Rates in Wealth and Non-wealth Tax Countries, Respectively, over 1980 to 2003

Hansson found the reasons for the above to be:

- Taxing wealth reduced the amount start-up capital available.

- The major motivator for entrepreneurs is after-tax returns, which is reduced by a wealth tax.

Charles Collocott

Researcher

charles.c@hsf.org.za

References

[1] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 17

[2] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 9

[3] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 786

[4] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 750

[5] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 833

[6] The Problem with a Wealth tax, Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2012

[7] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 13

[8] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 11

[9] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 749

[10] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 9 – 10

[11] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 775

[12] Wealth Under The Spotlight, 2015, pg 4

[13] Zucman, 2013

[14] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 13 – 14

[15] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 784 [10] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 19-20

[16] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 20

[17] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 20

[18] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 783

[19] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 19

[20] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 20

[21] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 742

[22] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 810

[23] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 20

[24] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 21

[25] Monika Lohmüller, 2012

[26] Ingé Lamprecht, 2016

[27] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 9

[28] Anna Iara, 2015, pg 14

[29] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 833

[30] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 787

[31] https://www.ft.com/content/19feb16a-1aaf-11e7-a266-12672483791a

[32] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 784

[33] Marius Brülhart, Jonathan Gruber, Matthias Krapf, Kurt Schmidheiny, 2016

[34] International Monetary Fund – Fiscal Monitor October 2017, pg 28

[35] Robin Broadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson, 2010, pg 787

[36] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 8

[37] International Monetary Fund – Fiscal Monitor October 2013, pg 39

[38] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 6

[39] Jan Schnellenbach, 2012, pg 20