Recent ANC Comments on Prescribed Assets for Financial Institutions - Brief I of II

Introduction

The idea of creating legislation that will force financial institutions to invest a fixed portion of their funds in state owned enterprises (SOEs) and government defined programmes, first arose at the ANC’s 2017 National Conference, where it was adopted that:

“Government should introduce measures to ensure adequate financial resources are directed to developmental purposes. A new prescribed asset requirement should be investigated to ensure that a portion of all financial institutions funds be invested in public infrastructure, skills development and job-creation.”

The Association of Savings and Investment South Africa (ASISA) stated that they have been given an indication by the ANC that it would make government bonds and SOE debt (guaranteed and non-guaranteed) form the prescribed assets.

Why is the ANC considering prescribed assets?

In an interview recently aired on the investigative journalism television show Carte Blanche, head of the ANC sub-committee on economic transformation, Enoch Godongwana, commented on the decision by Nedbank and Standard Bank made last year to stop funding new coal power projects, that “[t]o me, that’s an invitation for prescribed assets.”[1] Godongwana’s attack on the banks was prompted by an announcement by Eskom that new mines are not opening quickly enough to supply its power plants.

The policy of prescribed assets was further advanced in the ANC’s 2019 Election Manifesto:

“Investigate the introduction of prescribed assets on financial institutions’ funds to mobilise funds within a regulatory framework for socially productive investments (including housing, infrastructure for social and economic development and township and village economy) and job creation while considering the risk profiles of the affected entities”.

Briefly put, the ANC is considering putting in place legislation that will force financial institutions to invest a predetermined percentage of their assets under management in state-mandated areas and/or companies. The motivation ultimately stems from the fact that a number of large SOEs are failing to raise sufficient funding in the open markets. In 2017 SOEs experienced negative net issuance by redeeming R1.1 billion more outstanding debt than they issued. Although net SOE debt issuance in 2018 was a positive R5.7 billion, this was still far less than required.[2]

Quite apart from anything else, the comments by Godongwana also appear completely out of touch with developments in the power sector, leading to a much smaller role for coal generated power. The decommissioning process of ageing coal plants is progressively underway and the plan recommended in the draft 2018 Integrated Resource Plan only envisages an additional 1 000MW of coal power up to 2030 in comparison to the 39 216MW already available in 2018.

The South African Government had a policy of prescribed assets in the past, which lasted around three decades from 1956 until 1989. It was put in place because the state was cut off from global financial markets. During apartheid, global investors refused to invest in South Africa due to sanctions intended to apply pressure to the apartheid regime. Today, investors are refusing to invest in a number of South Africa’s SOEs – as seen by Eskom’s failure to raise enough capital in the open market – due to mismanagement, corruption and ultimately its junk status investment rating.

The history of prescribed assets in SA and the lessons learned

At its height, the Pension Funds Act of 1956 held the prescribed asset levels to be 75% for public investment commissioners and 33% for long-term insurers. This was to be invested in the debt of state-owned companies and government bonds.[3] The consequences for the savings industry varied over the decades, but ultimately it resulted in eroding investor wealth.

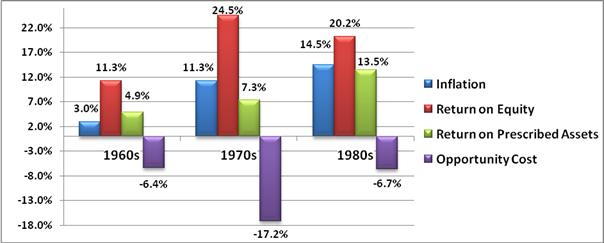

During the 1960s, when inflation was around 3%, prescribed assets gave a positive real return. But in the 1970s, inflation averaged 11% and the prescribed asset real return was negative 4%. During this time the stock market returned an average of 24.5% per annum, resulting in a negative 17.2% opportunity cost in nominal terms (including inflation) from investing in prescribed assets instead of the stock market. In the 1980s inflation averaged 14.5%, the real return for prescribed assets was negative 1%, and the nominal opportunity cost of not investing in the stock market was negative 6.7%.[4] This is shown graphically below:

The liquidity of bonds was also affected by the policy of prescribed assets. Bonds were valued at the lower of their cost or redemption value, resulting in big discounts in their pricing and hardly traded, because investors did not want to sell a bond at a loss. If they did, they would have to buy more to top up on their prescribed requirements.

With regards to the effect the policy had on asset allocation, around 40% of pension fund assets were in prescribed assets in the mid-to-late 1980s. Then, after the policy was abolished in 1989, the allocation to government bonds and SOE debt fell with a shift towards equities, and is currently near 20%.

In 1988 the Jacobs Committee was appointed to investigate prescribed assets and several associated market distortions, with the Committee ultimately recommending that the policy be scrapped.[5]

Is it lawful?

The Chief Investment Officer of one of the South Africa’s largest private sector investment funds, Andrew Canter from Futuregrowth Asset Management, has stated that a move by government to promulgate prescribed assets legislation will result in a constitutional challenge, because it is a violation of property rights as enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Notwithstanding the amendment to the property clause currently under way, constitutional law expert Pierre de Vos says that such a challenge is not so clear cut, because what will have to be proven is an arbitrary deprivation of property. De Vos goes on to say that “Even if you think the policy is [highly undesirable], it may not be arbitrary.”[6]

Is a policy of prescribed assets required?

In the above Carte Blanche interview, Godongwana went on to say “Who determines Policy? A government of the day determines policy. You can’t therefore have individuals determine what is the policy for the country.” What this kind rhetoric shows is a misunderstanding of the private sector’s willingness to invest in well managed SOEs and well thought out government programmes.

SOEs like the Landbank, the Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA) and the Trans Caledon Tunnel Authority (TSTA) have been able raise their required funds in the open market, even without government guarantees. The Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPP) programme managed to attract over R200 billion in just three years. And Treasury’s Jobs Fund, with 90% of its funding coming from the private sector, resulted in an investment vehicle that created over 9 200 jobs in the last three years.[7]

Given that there is in fact appetite for well conceived public investment programmes, what government should be doing is asking why they have not been able to raise funds in the required areas, and work to fix those disincentives, before considering apartheid-era style measures such as prescribed assets in order to avoid the discipline of the financial markets.

Charles Collocott

Policy Researcher

Charles.c@hsf.org.za

[1]https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2019-05-06-anc-wants-to-force-banks-to-invest-in-new-coal-mines/

[2]https://www.iol.co.za/personal-finance/investments/opinion-prescribed-assets-lessons-from-the-past-20092007

[5]https://www.iol.co.za/personal-finance/investments/opinion-prescribed-assets-lessons-from-the-past-20092007