Funding Government And State Owned Enterprises V - Pension Funds Not Regulated By The Pension Funds Act (2)

The series deals with the following topics:

- Introductory brief.

- Pension funds.

- Funds regulated by the Registrar of Pension Funds.

- The Government Employees Pension Fund and other public sector funds not regulated by the Registrar of Pension Funds (1)

- The Government Employees Pension Fund and other public sector funds not regulated by the Registrar of Pension Funds (2)

- Funds other than pension funds which might be required to finance SOE’s

- Country comparisons (1).

- Country comparisons (2).

- Conclusion.

Briefs 1 and 9 summarize the approach and findings, and they will be published first. Shortly thereafter, Briefs 2 to 5 will be published, and finally Briefs 6 to 8.

Introduction

A pension fund’s balance sheet typically consists of assets in the form of investments and reserves, and liabilities in the form of current and future benefits to be paid.

Government Employee Pension Law, 1996 (GEP Law) requires an actuarial valuation of the Government Employees Pension Fund’s (GEPF) assets and liabilities be conducted every two years. The funding levels, assets divided by liabilities, resulting from actuarial valuations are used to try and provide an indication of the financial health of the fund.

This brief therefore begins with an overview of the GEPF’s latest actuarial valuation, as well as the recommendations made by the third party actuaries who made the valuation. We then discuss possible reasons as to why the recommendations have not been taken up by the GEPF boards, as well as an analysis of some of these reasons.

An overview of the GEPF’s latest actuarial evaluation

As well as requiring an actuarial valuation of the fund’s assets and liabilities every two years, GEP law stipulates the different funding levels the fund is required to try achieve and maintain:

- The minimum funding level equals the fair value of assets divided by liabilities, excluding contingency reserves (held to buffer unknown risk events). GEP Law requires a minimum funding level target of 90%.

- The long-term funding level is the fair value of assets divided by the total liabilities, including contingency reserves. GEP Law requires a long-term minimum funding level target level of 100%.

The latest GEPF valuation, conducted by Alexander Forbes and published in 2019, reflected the fund’s position as at 31 March 2018 and shows a decline in short and long-term funding levels:

|

March 31, 2018 R'm |

March 31, 2016 R'm |

March 31, 2014 R'm |

|

|

Fair value of assets (A) |

1 800 068 |

1 629 923 |

1 425 719 |

|

Total accrued service liabilities (B) |

1 662 640 |

1 407 177 |

1 173 516 |

|

Total value of contingency reserves |

720 893 |

647 048 |

541 375 |

|

Total long-term liabilities (C) |

2 383 533 |

2 054 225 |

1 714 891 |

|

Minimum funding level (A/B) |

108.30% |

115.80% |

121.50% |

|

Long-term funding level (A/C) |

75.50% |

79.30% |

83.10% |

The 2018 minimum funding level of 108.3% is 18.3% above the 90% minimum funding target, but the long-term funding level of 75.5% falls well below the 100% target.

Given the decline in funding levels and based on an assumption of 5% future equity returns over their long-term bond yield assumption, Alexander Forbes recommended that the employer contribution rate be increased as follows:

|

Employer contribution rates |

||

|

March 31, 2018 |

||

|

Services staff |

Other |

|

|

Current rate |

16% |

13% |

|

Recommended rate |

18.9% |

14.4% |

As it turns out, the GEPF boards have never followed the auditors’ recommendations to increase the contribution rate,[1] and, because no indication has been given to the contrary, it is likely that they will not follow it once more.

Does this mean that, given the long-term funding levels currently below target, the board are idly standing-by while the GEPF runs out of funds to pay pensioners their future benefits? In an attempt to answer this question we will first consider some of the current risks facing the fund.

Risks to the GEPF’s funding level

First, the fair value of the fund’s assets (total funds and reserves) includes net investment income. However, in the 2019 annual report by the GEPF’s fund manager, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), there is no detailed disclosure of listed and unlisted investments, bonds, loans, and unpaid interest. Apart from a R121 million unrealised loss on investments mentioned by the Auditor-General (AG) in his audit report, it is unclear whether any further impairment to non-performing loans and unlisted investments were made.

Relying on the PIC information for an accurate fund valuation, the GEPF may therefore not have properly accounted for impairments on loans and unlisted investments. In fact, the GEPF’s accounts receivable as at March 2018 includes investment debtors of R2.2 billion, presumably reflecting unpaid interest and dividends on the unlisted loans and investments. As such, the GEPF runs the risk that the net investment income and the value of the fund along with it have been overstated for 2018.[2]

Second, in their long term return on investment forecast for the fund, Alexander Forbes used a 5% equity premium over their long-term bond yield assumption. However, the PIC invests according to a mandate received from the GEPF which is not driven by high absolute returns, but rather a liability driven approach that also uses a market related benchmark, specifically the JSE SWIX All Share Index.

As the world’s economy faces a possible economic slowdown – due to ongoing trade wars, a slowdown in emerging markets growth (most notably China), conflict in the Middle-East and Brexit – combined with tough market conditions locally, is a 5% equity premium perhaps too optimistic? If so, returns will be lower than forecast and the GEPF’s long term funding level will deteriorate further than expected.

Third, in order to try and downsize South Africa’s public sector payroll, which now consumes 14% of GDP, government has offered civil servants an early retirement option which allows the transfer of retirement funds out of the GEPF to other fund managers. This risk has not yet materialised, as recent data from Stats SA shows that employment levels in government have instead grown over the 12 months to the end of the second quarter of 2019.

If however government ups the ante on this plan – which it might do in order to decrease the state wage bill in trying to avoid a ratings downgrade – and civil servants increasingly start embarking on early retirement and the fund transfer option, an actuarial assessment of the negative effect it will have on the GEPF funding levels should be conducted.

So, given these risks and the deterioration of the GEPF’s funding levels, why then have the GEPF boards not taken on the valuator’s advice to increase the contribution rates? A couple of the possible reasons are discussed below.

Allowing the GEPF funding levels to slide

One reason as to why the GEPF boards have not taken on the valuators advice – to increase contributions in order to shore up funding levels – may be that they have not taken the legally imposed funding levels seriously.

A funding level of 100% means that the fund’s assets are enough to pay the present-value of all its liabilities, current and future. So should the retirement fund immediately cease to operate, its assets would be enough for all the fund’s members to receive their expected pension payments from that day on, right up until the day they die.

The reality is, however, that no fund is required to pay the present-value of all liabilities to its members on a single day. It is for this reason that the GEP Law sets the minimum funding level at 90% instead of 100%. In fact, the credit rating agencies Standard & Poor and Fitch will only regard a public pension’s funding level as weak if it falls below 60%.

It is therefore possible that the GEPF boards took the above into consideration when they repeatedly chose not to take on the auditors’ advice to increase the employer contribution rate – which, at an average of 13.5% of the employee’s salary, is already almost double the 7.5% average rate for private pension schemes.[3]

Another possible reason why the board have not taken on the advice is that they believe that the fund’s financial health should not be reduced to a single benchmark at a single point in time. Therefore, the board may have taken a number of other factors into account over different periods, and come to the conclusion that given these, there has been no need to increase the contribution rates.

To shed more light on this possibility we turn to brief released by the American Academy of Actuaries (AAA) in 2012, The 80% Pension Funding Standard Myth.[4]

According to the AAA, actuarial funding methods are generally designed to target a 100% minimum funding level. If it is less than this, the actuaries will advise that contributions be structured to obtain 100% funding over a reasonable period. However, the AAA has found that funding level measures above the minimum does not necessarily imply adequate funding and that the minimum funding levels might not be sustainable if:

- The fund’s obligations are excessive relative to the financial resources of the plan sponsor;

- The investments are excessively risky; or

- If the sponsor fails to make required contributions.

The AAA further found that because a funding level is a measure taken at a single point in time, it can vary significantly from year to year as a result of external events. Therefore, funding levels should be analysed over several years to determine trends, and should also be viewed in context of the prevailing economic circumstances over each period.

Whether a funding shortfall affects the financial health of a pension depends on many factors, particularly the size of the shortfall versus the resources of the plan sponsor. In this case the South African government.

Other factors the AAA says might be considered when assessing the health of a pension fund include:

- Size of the pension obligation relative to the financial size (measured by revenue or assets) of the plan sponsor.

- Financial health of the plan sponsor, for example debt levels, cash flow and budget surplus.

- Funding or contribution policy and whether contributions are actually made according to the plan’s policy.

- Investment strategy, including volatility risk and the possible effect on contribution levels.

An application of the American Academy of Actuaries’ findings to the GEPF

The GEPF’s long-term funding shortfall currently stands at well over R 563 billion. This amount must be compared to government’s finances as the plan sponsor, as discussed further below. We will now go through the other factors suggested by the AAA.

- From 2014 until 2018 the trend in the GEPF funding levels has been downward.

- The GEPF’s accrued service liabilities comes to R1.66 trillion and its long term liabilities close to R2.38 trillion. These figures are to be measured against the following from the plan sponsor, government:

- The expected tax revenue shortfall is R84bn in 2020/21 and R114.7bn in 2021/22.

- Government’s budget has been in deficit since 2008 and is expected to be 4.2% of GDP for 2018/19.

- Government’s gross loan debt reached an estimated R2.81 trillion or 55.6% of GDP in 2018/19 and Treasury expect it to stabilise at 60.2% of GDP by 2023/24. Other notable commentators see the debt to GDP ending up much worse levels. Former Treasury official Michael Sachs foresees it ending up at 80% within ten years.[5]

- Though contributions to the GEPF have been made according to policy, that policy has not been adjusted in-line with the valuator’s recommendations made in order to raise the funding levels to their targets.

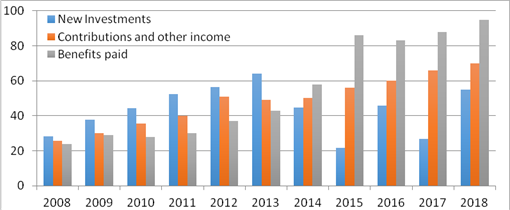

- Over the last five financial years and for the first time in the GEPF’s history, three important financial indicators have decoupled; cash flow out of the fund in the form of benefits paid has exceeded cash inflows from contributions, and new investments have decreased. The figures below are in R billion:

Nowhere within the GEPF’s annual reports is there an explanation for the drop in new investments. The drop raises the question as to whether this will translate into a decrease in investment returns that will apply pressure onto the future funded status.

With regards to the volatility of the GEPF’s investment returns, the average standard deviation of the returns for the past 10 years stands at 7.85, which is at the middle to lower end of standard deviation for OECD member country pension funds.

However, the standard deviation should not be measured in isolation but against the returns of the fund. This is done to gauge whether or not the returns were sufficient given the volatility/investment risk taken.

The standard practice for measuring a risk adjusted returns used by investment professionals is called the Sharpe ratio, which equals the fund’s return minus the risk-free rate of return, divided by the standard deviation of the returns of the period. A Sharpe ratio of 1 or above is good, 2 or above is very good, 3 or above is excellent, and a negative ratio does not convey any useful meaning.

The Sharpe ratios for the GEPF since 2008 have been:

|

GEPF Return % |

Risk Free Rate % |

Std Dev of Return ’08-‘18 |

Sharpe Ratio |

|

|

2008 |

6.70 |

8.11 |

7.85 |

-0.18 |

|

2009 |

-10.20 |

8.68 |

7.85 |

-2.41 |

|

2010 |

19.70 |

8.55 |

7.85 |

1.42 |

|

2011 |

12.20 |

8.24 |

7.85 |

0.51 |

|

2012 |

11.90 |

7.22 |

7.85 |

0.60 |

|

2013 |

16.00 |

7.21 |

7.85 |

1.12 |

|

2014 |

12.50 |

8.05 |

7.85 |

0.57 |

|

2015 |

10.20 |

8.15 |

7.85 |

0.26 |

|

2016 |

4.00 |

9.01 |

7.85 |

-0.64 |

|

2017 |

4.30 |

8.75 |

7.85 |

-0.57 |

|

2018 |

8.50 |

8.71 |

7.85 |

-0.03 |

Only on two occasions in the last eleven years was the GEPF’s risk adjusted return been good, i.e. its annual return given the volatility/investment risk taken on by the fund.

In summary, the GEPF does not fare well in any of the factors the AAA suggests one should consider when assessing the health of its funding levels.

Conclusion

The GEPF’s funding level has trended downward since 2014, and its boards have not taken on the actuaries’ recommendations of increasing contribution rates in order to bring it to the levels required by GEP Law. However, even if one gives the board the benefit of the doubt, as we initially did above, a further analysis of the possible reasons for the board’s lack of concern for the deterioration of the financial health of the fund does not support the boards’ actions.

With the GEPF’s funding levels in a downward trend and its sponsor, government, facing serious financial constraints of its own, the least the GEPF board can do is communicate clearly its reasoning for allowing the slide to continue. If government is required down the line to step-in to cover a funding short-fall, it is reasonable to wonder whether or not it will have the funds to do so.

Charles Collocott

Policy Researcher

charles.c@hsf.org.za

[1]https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-08-29-the-government-employee-pension-fund-budget-austerity-and-the-eskom-debt-crisis/

[3]https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-08-29-the-government-employee-pension-fund-budget-austerity-and-the-eskom-debt-crisis/

[4] American Academy of Actuaries, Issue Brief, July 2012, The 80% Pension Funding Standard Myth.