Financing The Public Sector Borrowing Requirement Should South Africa Attempt Yield Curve Control?

The 2020 Budget estimated that the total public sector borrowing requirement (“PSBR”) for the 2020/21 financial year would be R 454.1 billion. Of this R 370.5 billion would be needed for ‘consolidated government’, R 73.2 billion for state owned enterprises and R 10.4 billion for local authorities. It is the consolidated government component with which we are concerned here. State owned enterprises and local government incur debt on the basis of their balance sheets. By contrast, consolidated government borrowing finances (a) requirements on operating accounts (R 141.2 billion), (b) requirements on capital accounts (R163.4 billion) and (c) the balance of transactions in financial assets and liabilities (R61.0 billion).

It is certain that the consolidated government requirement will be substantially greater than estimated in the budget for two main reasons. The first is the increase in government expenditure associated with the coronavirus, including expenditure on income support and the second is the decline in government revenue resulting from reduced levels of economic activity and tax concessions. This means that the government will either have to issue more bonds, or borrow directly from abroad, notably from the International Monetary Fund.

Since 14 January 2020, the government has been raising R 4.53 billion per week from sale of fixed rate government bonds, and a further amount from the sale of inflation linked bonds (at a rate of R 1.04 billion per week in January). Tranches of three fixed rate bonds and three inflation linked bonds are auctioned each week, and the mix varies from week to week. A rate of R 5.57 billion per week will not suffice to meet the 2020/21 PSBR, as estimated in the Budget, let alone the expected increase.

The yield curve

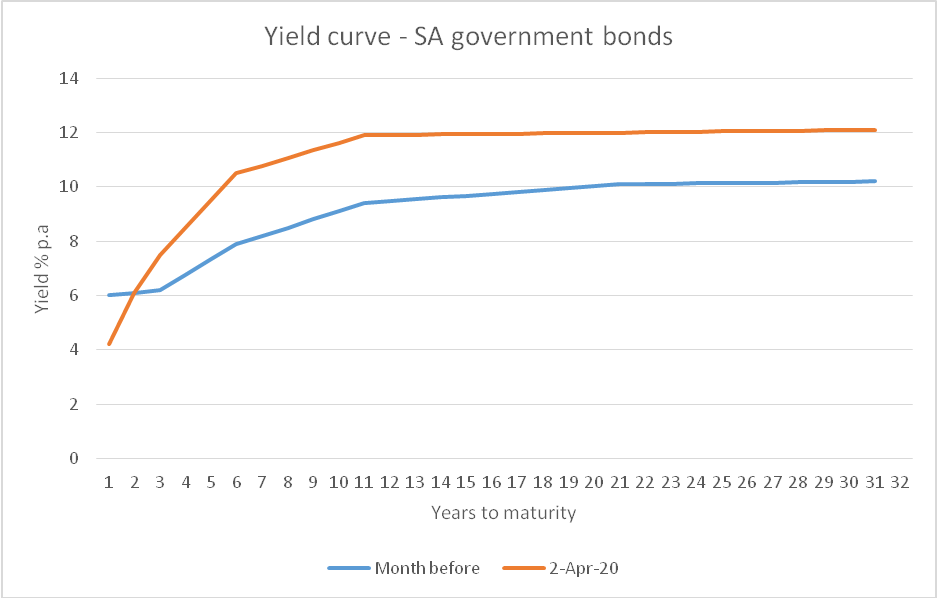

A yield curve is a line that plots yields (interest rates) of bonds having equal credit quality but differing maturity dates, against the time to maturity. A normal yield curve is one in which longer maturity bonds have a higher yield compared to shorter-term bonds due to the risks associated with time.

The chart below graphs the yield curve on 2 April 2020 and a month earlier.

Source: World Government Bonds

Relative to a month ago, yields have dropped for bonds with short maturities. This is in large part an outcome of the repo rate cut of 1% on 19 March. But yields have risen substantially on bond with more than two years to maturity. Bond prices vary inversely with yield, so a higher yield implies a lower price achieved at auction.

On 22 March, the Reserve Bank announced that it would be buying government bonds in order to provide liquidityand promote the smooth functioning of domestic financial markets. It added that the amount and maturity of the bond purchases will be at the discretion of the Bank. Bonds rallied after the central bank’s announcement. The yield on 10-year government debt was 12.36 per cent on 24 March, reflecting a drop in prices, but fell to 11.44% on 3 April. To the extent that purchases are financed by the creation of new money, the effect will be to stimulate the economy. Equally, sales could be used to drain liquidity and decrease the money supply.

The smooth functioning of domestic financial markets require that peaks and troughs in government bond yields (more likely peaks at the moment) are smoothed out. We can expect spikes in the coming weeks partly in response to coronavirus developments and their associated effects on the PSBR and partly because of adjustment to the consequences of the Moody’s downgrade of 24 March, necessitating sales of some bonds held by foreigners. But the question arises: will the Reserve Bank attempt to lower the yield curve at longer maturities more permanently and, of so, what the effect will be.

Yield curve control and quantitative easing

Yield curve control (“YCC”), also known as interest rate pegging, is the policy of setting target yields at one or more times to maturity, with the Reserve Bank buying or selling bonds in quantities designed to achieve these yields. The only country to use it up until recently is Japan, which introduced it in September 2016 with the aim of holding the yield on its ten year government bond to zero. YCC has also been used in war time, and was used from 1942 in the United States. Discussion of its application in countries other than Japan is now under way.

Two questions arise. The first is whether yield curve control and quantitative easing (‘QE’) are the same. Like quantitative easing, yield curve control involved central bank purchase of government bonds. Generally, the term QE describes any policy that increases the central bank’s liabilities. But QE in general does not imply YCC, because it does not require the setting of yield curve targets. QE works through two channels. The first is when investors replace government bonds they sell to the Fed with other, riskier assets. The prices of those assets rise, helping to stimulate business and consumer spending. The second way QE helps to lower market interest rates is by signaling that the central bank plans to keep policy rates low for a long time.

For YCC to work, it has to be credible. If investors believe the central bank will stick to this program for the full duration of the relevant assets, then they will begin trading those securities at a price consistent with the peg, because they will be confident in their ability to sell or buy at that price again before the asset matures. What is more, if expectations stabilize, the central bank may not have to purchase much at all. The Bank of Japan has found that YCC has entailed fewer bond purchases than its earlier QE policies. However, if the peg is not credible, investorswould be less willing to buy bonds at the pegged price, and the central bank would have to purchase large amounts of bonds, with the risk that monetary expansion induces demand led inflation. Lack of credibility increases with (a) the time to maturity of the pegged bond (b) the number of bonds (with different times to maturity) where pegs are imposed, and (c) the uncertainty about the trajectory of the economy. For these reasons, the Reserve Bank is unlikely to go beyond short term stabilization, eschewing attempts to depress the stabilized yield curve.

Conclusion

The real alternative to expensive finance resulting from sale of bonds with long terms to maturities is a turn to foreign loans. South Africa has already decided to take a US $ 1 billion loan from the New Development Bank, and the National Treasury is looking for cheap money around the world. An option is engagement with the International Monetary Fund, which is offering Rapid Financing Instrument loans at a low dollar rate of interest over a three to five year period. To compare the cost of foreign loans with domestic finance, exchange rate risk has to be taken into account. Ideally, one would want to draw down the loan when the dollar to rand exchange rate reaches its worst point, especially as exchange rates overshoot. But no-one rings a bell at the bottom, so the best one can hope for is good judgement about timing.

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

charles@hsf.org.za