Do We Have an Adequate Measure of Hunger in South Africa? I - the General Household Survey

Introduction

The relief of hunger is often cited as a reason for the introduction of the social relief of distress grant. What do we know about the extent of hunger? How complete and coherent is the available information?

There are two national surveys which collect data on hunger:

- The General Household Survey, conducted once a year. The most recent year for which data have been published is 2019. Release of the 2020 GHS is scheduled for 28 October 2021.

- The five waves of the National Income Dynamics Study’s Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey covering five of the months between April 2020 and March 2021.

This brief will discuss the 2019 GHS. The NIDS-CRAM results will be considered in the next brief.

Conceptual framework

The Food Security section of the GHS questionnaire uses a shortened version of the Household Food

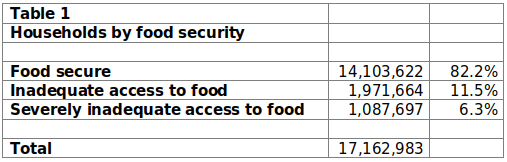

Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)[1]. The HFIAS is an adaptation of the approach used to estimate the prevalence of food insecurity in the United States (U.S.) annually. The questions in the GHS are set out in the Annexure. They are used to compute a household food security index from each of the two components of questions FSD5 to FSD8. Affirmative answers to these questions are counted up, yielding a score of zero to eight. Households with a score of zero or one are classified as food secure. Households with a score between two and five are classified as having insecure access to food and households with a score between six and eight are classified as having severely insecure access to food. Table 1 set out the distribution of households across these categories.

Households are regarded as vulnerable to hunger if any of their members have sometimes, often or always experienced hunger in the last twelve months. In 2019, 1,750,650 were vulnerable, or 10.3% of all households for which the relevant information was available. Between 2007 and 2019, the percentage of vulnerable households has varied between 9.7% (in 2018) and 11.6% (in 2011), roughly constant when sampling error is taken into account[2].

When interpreting data on experience during the last twelve months, two household instabilities should be borne in mind: variation in personal composition, and variation in household income over the period.

Along the way, the data can and should be checked for coherence.

The population, as estimated by GHS19, was 58,428,892 and the number of households was 17,162,983, giving an average household size of 3.40.

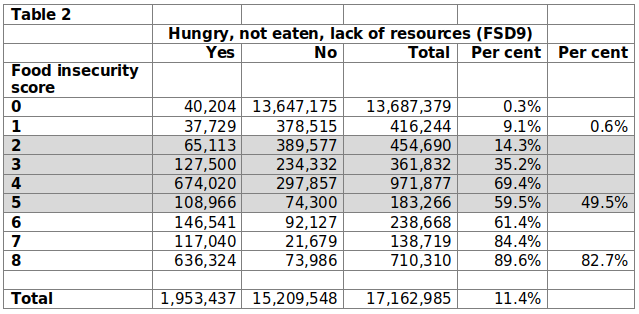

Table 2 sets out the relationship between the responses to FSD9 and the food insecurity index. When sampling error is taken into account, the percentage of households answering FSD9 in the affirmative rises as the food insecurity score rises.

The basics, including frequency of hunger and impact of the lack of resources on hunger

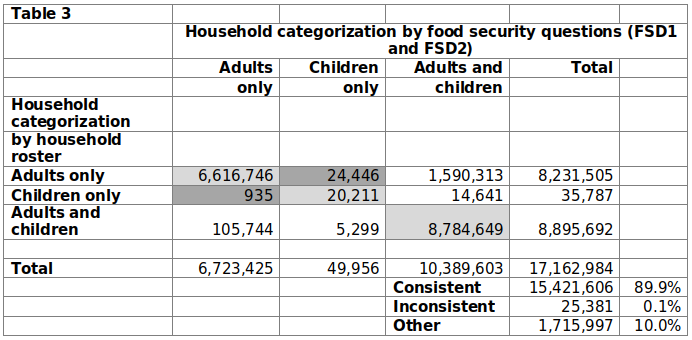

Households can be divided into three categories: households where only adults are present, households where only children are present, and households containing both adults and children. Classification of households are possible using household rosters. To qualify for inclusion in a household roster, a person must have spent at least four nights on average per week for the four weeks before being surveyed. The data on frequency of hunger among adults and children also permit the classification of households, his time by presence over the last twelve months. The two classifications are compared in Table 3.

The lightly shaded entries are consistent. The dark shaded entries are clearly inconsistent or reflect missing food security data. The status of the entries in the unshaded areas is unclear: either household composition has changed during the twelve months before the survey or there are errors in the data.

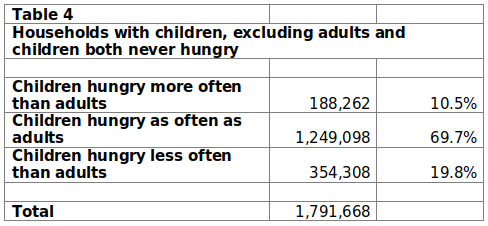

Table 4 shows the relationship between the frequency of child hunger and the frequency of adult hunger in households where both adults and children were found using questions FSD1 and FSD2. Households in which neither an adult nor a child was ever hungry are excluded. Shielding is said to occur when at least one adult subjects themselves to a greater frequency of hunger than at least one child, and occurs in 20% of households. In 70% of households, at least one adult and at least one child are reported to experience the same frequency of hunger and in 10% at least one child experiences hunger more frequently than at least one adult.

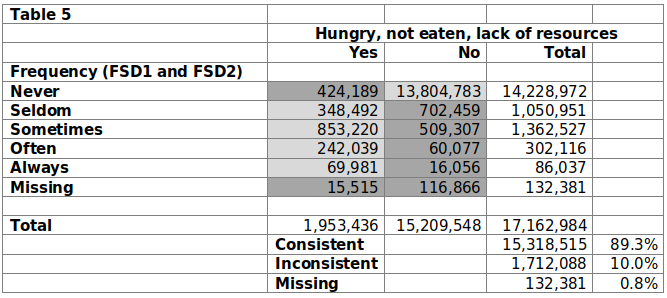

One can use the responses to the questions about the frequency of adult hunger and child hunger to categorize the frequency of household hunger by replacing the frequency of adult hunger with the frequency of child hunger when the latter is available and exceeds the former. Households categorized in this way are cross-tabulated in Table 5 against responses to the question whether anyone in a household has been hungry and not eaten because of lack of money or other resources to buy food. As in Table 3, the lightly shaded entries are consistent, the dark shaded entries are inconsistent. Like Table 3, Table 5 demonstrates inconsistencies between the answers to FSD1 and FSD2, on the one hand, and FSD9 on the other.

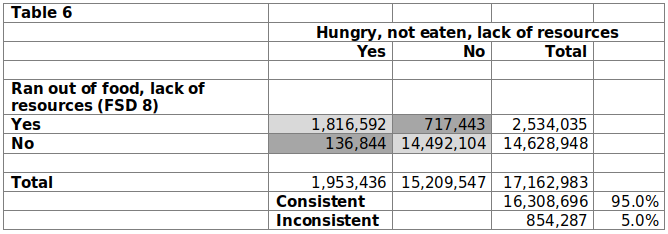

Table 6 cross-tabulates households by whether the respondent or others were hungry but did not eat because of lack of resources and whether households ran out of food because of lack of resources.

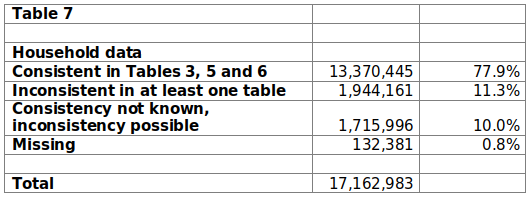

The evidence on consistency across all Tables 3, 5 and 6 is summarized in Table 7.

Anxiety about not having enough food to eat

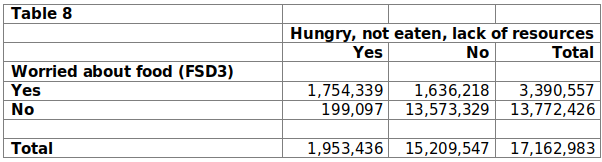

Table 8 cross-tabulates households which reported whether they had worried about not having enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources against whether they had been hungry and not eaten. It may be that had some households which reported worry and did not experience hunger, would have experienced it had they not worried.

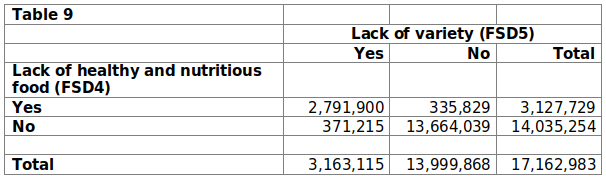

Lack of food variety and lack of healthy and nutritious food

Table 9 cross-tabulates households which reported that they had lacked healthy and nutritious food against whether they had lacked variety in their diet. As expected, most entries are on the diagonal, but some households reported that they had not lacked healthy and nutritious food while lacking variety in their diet and others reported that they had not lacked variety but had lacked health and nutritious food.

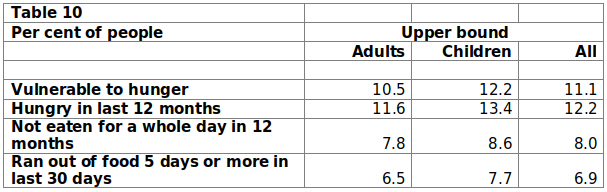

People living in households where someone has been hungry by four different measures in the past year or past month

Up to this point, the unit of observation has been the household. It is possible to calculate the number of adults, children and all people in households experiencing hunger according to four measures, on the assumption that, if there is hunger in a household according to any measure, all people in the household experience it on that measure. These calculations lead to upper bound estimates. On all measures, the percentage of children in households experiencing hunger is slightly higher than the number of adults experiencing hunger.

The proportion of vulnerable people has drifted downwards from 13.8% in 2007 to 11.1% in 2019[3].

Conclusion

A full set of conclusions will be presented in the following brief, once data from NIDS-CRAM have been considered. But one point can be made here. The GHS19 hunger data are suboptimal, in that they contain inconsistencies and unlikely combinations. Technology is now available which requires enumerators to eliminate inconsistencies as they emerge and to probe further if there are unlikely combinations. Using the appropriate devices will improve the quality of the data and resolve some of the uncertainties seen in this brief.

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

Annexure - GHS 19 Food Security Questions

FSD1 In the past 12 months, did any adult (18 years and older) in this household go hungry because there wasn’t enough food?

- Never

- Seldom

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

- Not applicable (no adults in household)

FSD2 In the past 12 months, did any child (17 years of younger) in this household go hungry because there wasn’t enough food?

- Never

- Seldom

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

- Not applicable (no children in household)

FSD3 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household worried about not having enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

FSD4 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household were unable to eat healthy and nutritious food because there was not enough money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

FSD5 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household ate only a few kinds of foods because there was not enough money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

Has it happened 5 or more days in the past 30 days?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

FSD6 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you and others in your household had to skip a meal because there was not enough money or other resources to get food?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

Has it happened 5 or more days in the past 30 days?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

FSD7 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household ate less than you thought you should because there was not enough money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

Has it happened 5 or more days in the past 30 days?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

FSD8 During the last 12 months, was there a time when your household ran out of food because of a lack of money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

Has it happened 5 or more days in the past 30 days?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

FSD9 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough money or other resources to buy food?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

FSD10 During the last 12 months, was there a time when you or others in your household went without eating for a whole day because of a lack of money or other resources?

- Yes

- No

- Do not know

- Refused to answer

[1] The scale is set out in Jennifer Coates, Anne Swindale and Paula Bilinsky, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide, USAID Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA III), August 2007

[2] Statistics South Africa, General Household Survey 2019, Statistical Release, P0318, 17 December 2020

[3] Ibid