Budget Challenges II: Public Debt

South Africa’s debt situation

Citing fast growing government debt as a one of four major factors hindering South Africa’s development, the IMF’s 2018 Country Report for South Africa opened with the following paragraph:

Amid a marked growth deceleration, some of South Africa’s economic and social achievements after the end of apartheid have recently unwound. While the economy is globally positioned, sophisticated, and diversified, gaps in physical infrastructure and education create large productivity differentials across sectors. Low consumer and business confidence has dampened productivity growth. Fast growing debt has constrained policy space. As a result, per-capita growth has turned negative, the poverty rate stands at around 40 percent, unemployment has crept up to 27 percent—almost twice that level for the youth—and income inequality is one of the highest globally.

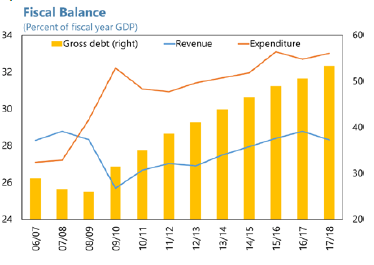

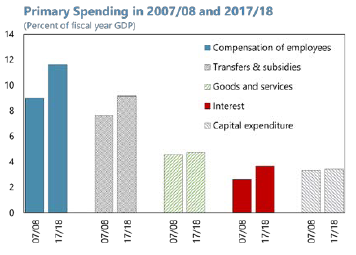

Off the back of strong economic growth in the decade after apartheid, government debt halved to less than 30 percent of GDP by the mid-2000s.[1] Since then the trend has reversed due to increases in primary government spending – especially on wages and salaries – and interest payments amid low growth.[2] Government’s compensation expenditure is higher than other emerging and middle-income countries, despite employing a smaller percentage of the working age population. Furthermore, government has not lowered its primary spending ceiling despite a significant downward revision in GDP growth.[3] Interest payments on government debt increased from 6.7 percent of revenue in 2008,[4] to 13.7 percent in 2017.[5]

South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio was last measured at 53.1 percent.[8] A recent study by the Centre for Global Development shows a statistically significant threshold effect in countries with rising debt-to-GDP ratios above 50-60 percent, where growth drops off and leads to default or debt restructuring.[9] Another study by the World Bank found the threshold debt-to-GDP level to be 77.1 percent. Beyond this, each additional percentage point in debt-to-GDP costs the economy 0.0174 percent in annual real growth.[10]

A couple of features of South Africa’s debt cushion its risk; the low share of foreign currency debt (9 percent) decreases exchange rate risk, and the low share in short-term debt (12 percent) as well as an average maturity at nearly 15 years decreases refinancing risk.

On the flip side, 40 percent of the total debt is held by non-residents. Should South Africa’s debt be rated below investment grade thereby excluding it from the global bond index, these non-resident bond holders will be forced to sell. Also cited as major debt risks are government’s contingent liabilities, having doubled in the last decade to 16 percent of GDP, and government guaranteed debt at R670 billion, or 10.1 percent of GDP.[11] Meeting a guarantee of say R100 billion in SOE debt would up the debt-to-GDP ratio by 2.13 percent.

A critical fact often missed by analysts is that due to cross-default clauses on SOE loans, SOE creditors whose debt is not guaranteed may threaten to ‘bring the house down’ if their loans are not serviced properly. Therefore government has to ensure that all loan commitments are honoured, whether guaranteed or not. In this regard, in 2018 government had to transfer around R5 billion to SAA and the post office[12] when they were unable to fully meet their debt servicing requirements.[13] Eskom’s latest guaranteed debt figure is R350 billion, with total debt close to R570 billion.[14] Combined SOE debt stands at R 868.9 billion.[15] The following extract from the IMF report raises concern around Eskom’s worsening indebtedness, increasing financing costs and risk to the state:

Despite the above-inflation tariff adjustments – in part to cover its investment program – Eskom produces at a loss and its paper is rated as sub-investment. Notwithstanding a R23 billion (0.5% of GDP) state bailout and the transformation of an earlier R60 billion (1.2% of GDP) subordinated loan into equity in 2015, and state guarantees of R350 billion (7% of GDP), Eskom has increased its reliance on financing from development finance institutions. Eskom’s debt to equity ratio is above 70% and it needs R60–80 billion (1½% of GDP) per year for the next five years to cover its capital spending. Eskom’s liquidity is under increasing pressures, and the spread on its international bonds is about 490 basis points relative to the benchmark as of end-June.

The IMF highlighted poor management of SOEs and that government guarantees ‘should be contingent on turnaround plans with well-specified implementation performance targets.’[16]

At the end of 2018 it was reported that Eskom chairman Jabu Mabuza, speaking in an interview during an investor road-show, proposed that government absorb R100 billion of its debt – in order to bring interest costs to a manageable level. In response to questions by the press on the matter, Treasury spokesperson Jabulani Sikhakhane saidgovernment’s policy stance is that funding for SOEs must be “done in a deficit-neutral manner.”[17] Given current pressures on the fiscus it is unlikely that a deficit-neutral approach would be possible. So what are the other avenues for taking R100 billion in debt off Eskom’s books?

First, government could raise cash by going into further debt itself, and transfer the proceeds to Eskom to retire the debt. Second, simply transfer the debt to government. Both these options would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by over 2%. Given the already worrisome debt levels of government described above, these options would not be desirable. Third would be for Eskom to attempt to sell equity in the open market, which is unlikely to succeed. Fourth, Eskom could ask its creditors to swap debt amounting to R100 billion for equity. In this scenario, consider Eskom’s largest creditor, the Government Employee Pension Fund (GEPF), whose assets are invested through the Public Investment Corporation (PIC). At the centre of the GEPF’s mandate, as with any pension fund, is the requirement that the beneficiaries’ funds are responsibly invested, and the value of the investment fund sufficiently protected.[18] So taking an equity stake in Eskom which is projected to make a loss of R20 billion in the next financial year, and without prospects of turning a profit in the foreseeable future, would fall outside of its mandate. The only possible scenarios in which the GEPF would take up the equity would be if it changed its mandate to include investments ‘for the greater good of South Africa’ in certain scenarios, regardless of the effect on its beneficiaries investment fund, or if were to no longer guarantee payouts to its beneficiaries in line with inflation.

South Africa compared to other middle-income countries

Appendix 1 contains a graphical depiction of South Africa’s position within several important macro-economic indicators versus a number of other middle income countries; namely debt-to-GDP, GDP growth, financing costs, non-resident debtors and foreign currency debt. What can be seen is that South Africa finds itself closer to the wrong end than the right end of the spectrum for all five of the indicators.

The IMF routinely carries out a public debt sustainability analysis as part of the staff analysis for Article IV consultations. The method is similar to the stress testing of commercial banks which has become widespread in the years following the financial crisis. A fiscal model is constructed and outcomes tested against adverse shocks or factors. The result is a ‘heat map’ showing the impact of each shock and factors on public debt sustainability, with individual responses assessed as low, medium or high. The outcome of the most recent analyses for South Africa, Argentina, Brazil, China[19] and Turkey are presented in Appendix 2.

When it comes to the debt level variables, South Africa’s profile is slightly worse than Argentina, China (narrow), and Turkey, but better than Brazil and China (broad). It is noteworthy than South Africa is the only country in the group where persistently low growth has been considered as a variable. When it comes to gross financing needs, South Africa and Turkey are equivalent, with other countries worse. On debt profile variables, South Africa is worse than China (narrow) and China (broad), slightly worse than Brazil, and better than Argentina and Turkey. Taking the seventeen variables together, it is clear that each country has its own particular profile, depending on past fiscal policy and the political circumstances which prompted it.

Conclusion

The economic environment requires a cautious approach to the Budget, as does the debt situation, which has been worsening by the year for most of the current decade. The government will need to provide convincing evidence that it has the primary budget deficit under control and that its contingent liabilities are under control. Neither will be a walk in the park.

Appendix 1

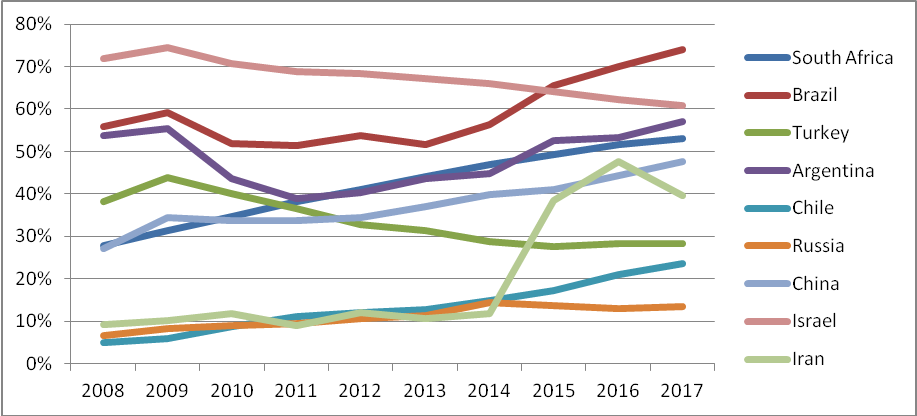

- Changes in the Debt-to-GDP ratio [20]

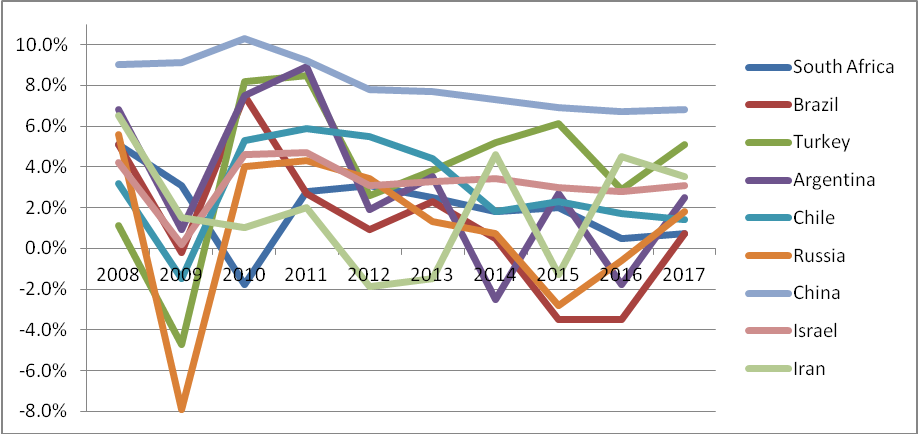

- Changes in GDP growth: [21]

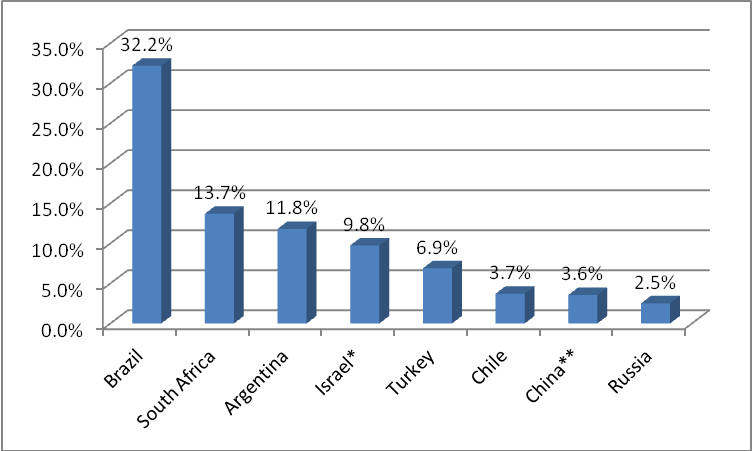

- Financing costs as a percentage of revenue Fiscal Year 2017: [22]

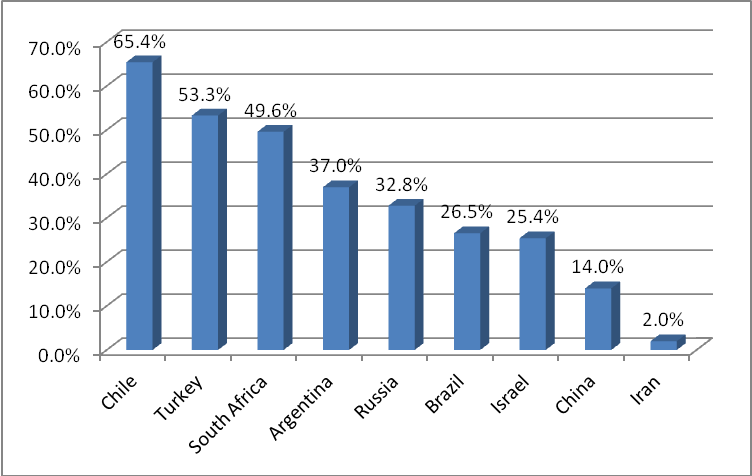

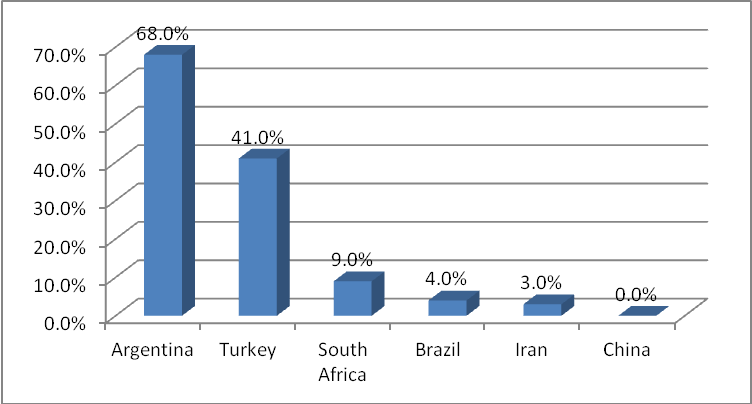

*2015, **2013. - Non-resident debt holders as a percentage of GDP Fiscal Year 2017: [23]

- Public debt in foreign currency Fiscal Year 2017: [24]

Charles Collocott

Researcher

charles.c@hsf.org.za

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

charles@hsf.org.za

Appendix 2 – Debt sustainability heat maps

|

Debt level |

|||||||

|

Real GDP |

Primary |

Real interest |

Exchange |

Contingent |

Persistently |

||

|

South Africa |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Argentina |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|||

|

Brazil |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

||

|

China (narrow) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

||

|

China (broad) |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|||

|

Turkey |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

||

|

Gross financing needs |

|||||||

|

Real GDP |

Primary |

Real interest |

Exchange |

Contingent |

Persistently |

||

|

South Africa |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Argentina |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|||

|

Brazil |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

||

|

China (narrow) |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

||

|

China (broad) |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|||

|

Turkey |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

||

|

Debt profile |

|||||||

|

Market |

External |

Change in the |

Public debt |

Foreign |

|||

|

South Africa |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

||

|

Argentina |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

Medium |

High |

||

|

Brazil |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

||

|

China (narrow) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

||

|

China (broad) |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Low |

||

|

Turkey |

Medium |

High |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

||

Article edited with the online wysiwyg HTML editor. Subscribe for a HTMLG membership to stop adding promotional messages to your documents.

[1] IMF Country Report No. 18/246, at 5.

[2] Op cit note 1 at 31.

[3] Op cit note 1 at 33.

[4] National Treasury Budget Review 2008 at 89.

[5] National Treasury Budget Review 2018 at 89.

[6] Op cit note 1 at 33.

[7] Op cit note 1 at 33.

[8] Op cit note 1 at 1.

[9] Op cit note 1 at 11.

[10] http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/509771468337915456/Finding-the-tipping-point-when-sovereign-debt-turns-bad

[11] National Treasury Budget Review, 2018.

[12] https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/business/2018-10-24-saa-post-office-and-other-ailing-soes-to-receive-billions-in-cash-bailouts/

[13] Op cit note 1 at 7.

[14] Eskom 2018 Integrated Report, at 15

[15] National Treasury Budget Review, 2018 at 106.

[16] Op cit note 1 at 26.

[17] https://businesstech.co.za/news/energy/289352/eskom-wants-government-to-absorb-r100-billion-debt-report/

[19] China has two measures of public debt: narrow, which includes includes central government debt and “on-budget” local government debt identified by the authorities, and broad, which adds other types of local government borrowing, including off-budget liabilities (explicit or contingent) borrowed by Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) via bank loans, bonds, trust loans and other funding sources, and also covers debt of government-guided funds and special construction funds,

[22] IMF.

[23] Op cit note 15.

[24] Op cit note 17.

[7]

[7]